Projects

Academic Projects (2017–2025)

Research projects completed during my PhD and postdoctoral positions, focusing on astrophysics and computational modeling.

During my time as a researcher, my academic work focused on cosmic dust — the tiny solid particles that pervade our galaxy and play crucial roles in star formation, planet building, and chemical enrichment of the Universe. Below, I present four key projects that illustrate my approach to solving complex, data-driven problems in astrophysics. Through these projects, I developed a strong expertise in radiative transfer modelling — the computational simulation of how light interacts with matter — which is essential for interpreting astronomical observations and constraining physical properties from complex datasets. Beyond the scientific domain knowledge, these projects honed my skills in Python code development, collaborative code development with international teams, parallelisation of computations on university clusters, machine learning techniques to reduce computational time, and visualisation techniques for complex, multi-dimensional datasets.

Project 1: Decoding the Winds of a Dying Star

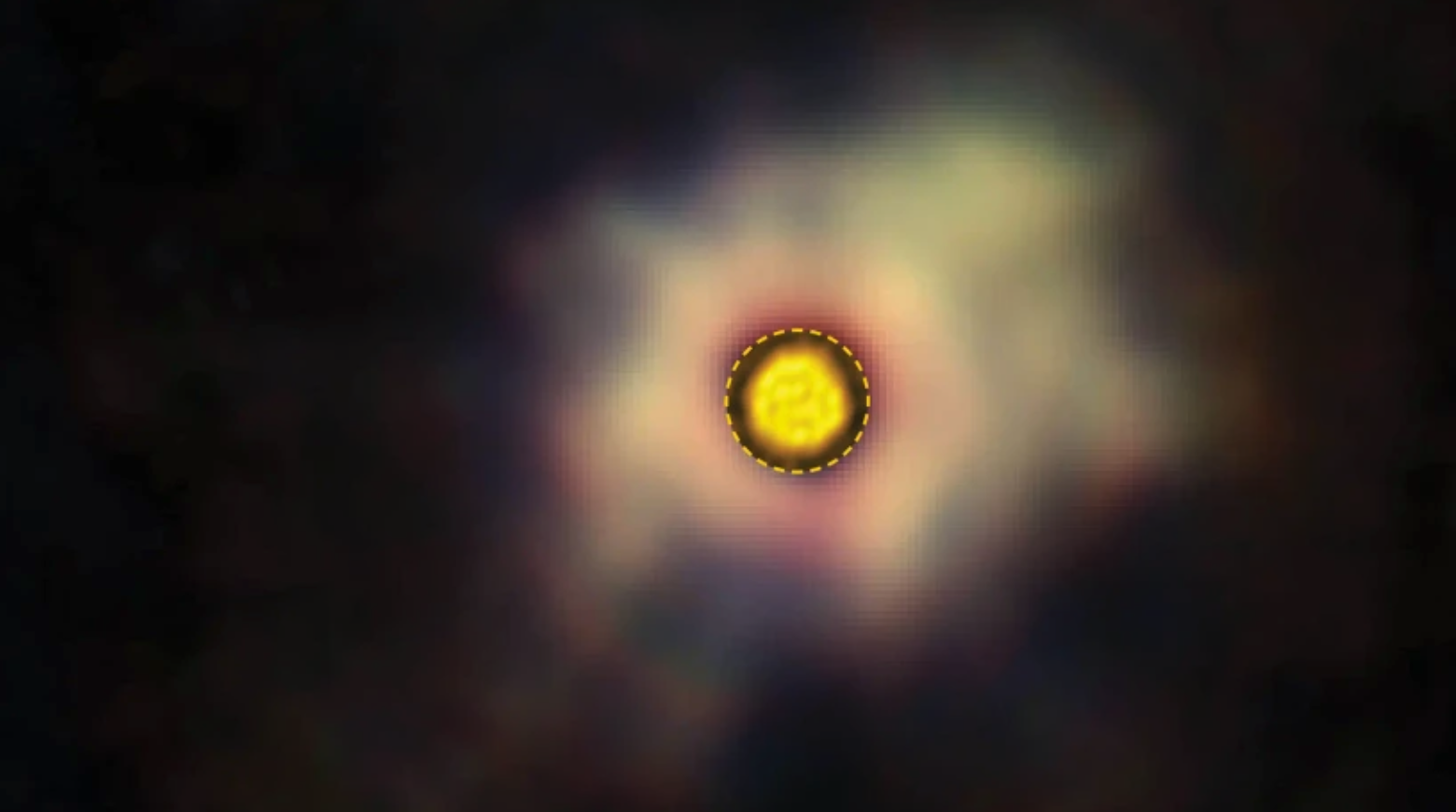

Constraining Dust Properties in the Atmosphere of R Doradus

The scientific context: why understanding stellar winds matters

Most of the heavy elements in the Universe — carbon, oxygen, silicon, iron — are forged inside stars and then released into space. This "cosmic recycling" is essential: without it, there would be no rocky planets, no organic molecules, and ultimately no life as we know it. But how exactly do these elements escape from stars and spread through the cosmos?

The answer lies largely with Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) stars — evolved, dying stars that have exhausted their core hydrogen and helium. These stellar giants are cosmic dust factories, producing massive quantities of dust grains in their extended atmospheres. The standard theory suggests that stellar light pushes on these dust grains (a phenomenon called radiative pressure), which then drag the surrounding gas along with them, creating powerful stellar winds that eject material into space.

R Doradus is one of the closest AGB stars to Earth (~55 parsecs, roughly 180 light-years away), making it an ideal laboratory to study these processes in detail. Its proximity allows us to resolve spatial structures in its atmosphere that would be impossible to see in more distant stars. R Doradus is also an oxygen-rich star, meaning it produces silicate dust grains — the same type of material found in rocky planets like Earth.

The research question: can dust drive the wind?

The central question was both fundamental and challenging: Can we determine the properties of dust grains forming around R Doradus, and assess whether these grains are capable of driving the observed stellar wind through radiative pressure alone?

This required solving a complex inverse problem: from observations of light at multiple wavelengths, we needed to infer the physical characteristics of dust grains (their size, composition, and spatial distribution) and then test whether the physics of radiation pressure could explain the mass loss rate we observe. The challenge was that the problem involves many coupled variables — dust properties affect how light propagates, which in turn affects the temperature structure, which affects where dust can form.

My approach: combining observations with computational modeling

Data integration from multiple observatories: I combined observations from three major facilities: the VLT/SPHERE/ZIMPOL instrument (providing high-resolution polarimetric images in visible light), ALMA (radio interferometry revealing the gas density structure), and archival photometric data spanning from optical to mid-infrared wavelengths. Each dataset provided complementary constraints — the polarization data is sensitive to scattering by dust grains, ALMA traces the gas distribution, and the spectral energy distribution (SED) constrains the overall dust mass and temperature.

Radiative transfer modeling: I used a sophisticated Monte Carlo radiative transfer code called RADMC-3D to simulate how light interacts with dust in the circumstellar environment. This code traces millions of photon packets as they scatter, absorb, and re-emit through the dusty medium, allowing us to compute synthetic observables (images, polarization maps, SEDs) for any given dust model.

Parameter space exploration with physical constraints: Rather than blindly searching a high-dimensional parameter space (dust composition, grain sizes, spatial distribution, mass-loss rate — a 6-dimensional problem), I implemented physics-based filtering to eliminate unphysical parameter combinations before running expensive simulations. For example, some parameter combinations would produce an optically thick medium — meaning light could not travel through it. But we clearly observe starlight from R Doradus, so such solutions are ruled out immediately. This pre-filtering saved an estimated several weeks of computation time while ensuring we explored only physically plausible scenarios.

Iterative fitting and validation: I compared synthetic observables from thousands of model runs against the real data, iteratively refining the parameter constraints. The model predictions were validated against multiple independent observations to ensure consistency.

Key findings: challenging the dust-driven wind paradigm

Tight constraints on dust properties: I successfully constrained the dust grain properties: a mixture of magnesium-iron silicates (MgFeSiO₄, specifically Mg₀.₅Fe₀.₅SiO₃) and transparent alumina (Al₂O₃) grains, with sizes around 0.3–0.5 micrometers. This is significantly larger than typical interstellar dust grains (~0.1 μm), suggesting that grain growth occurs efficiently in the dense inner atmosphere.

A fundamental puzzle: The most striking result was negative in a scientific sense, but extremely important: the dust grains we observe cannot drive the wind through radiative pressure alone. The momentum transfer from starlight to dust is insufficient by a significant factor. This challenges the long-standing paradigm of dust-driven winds for oxygen-rich AGB stars.

New directions: This finding opens exciting avenues for future research. Alternative mechanisms — such as giant convective bubbles in the stellar atmosphere, stellar pulsations, or episodic dust formation events — may play crucial roles in launching these winds. The result forces the astrophysical community to rethink the mass-loss mechanism for a significant fraction of AGB stars.

Impact: The paper was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025) and was featured in a Chalmers press release.

Project 2: Tracking Dust Evolution Under Extreme Radiation

Constraining Dust Properties in Photon-Dominated Regions

The scientific context: where starlight shapes dust

Photon-Dominated Regions (PDRs) are cosmic laboratories where intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation from massive stars sculpts the surrounding gas and dust. These regions are found at the interfaces between hot ionized gas (near the star) and cold molecular clouds — the birthplaces of new stars and planets. Think of them as the "weather zones" of the interstellar medium, where energetic stellar light creates dynamic, layered structures.

Dust grains in PDRs play multiple critical roles in astrophysics: they catalyze the formation of molecular hydrogen (H₂, the most abundant molecule in the Universe), they absorb UV photons and re-emit energy in the infrared (affecting the thermal balance of the gas), and they heat the gas through the photoelectric effect — UV photons eject electrons from grain surfaces, and these energetic electrons collide with gas atoms, transferring energy. All of these processes depend sensitively on the dust properties: size distribution, composition, and structure.

Understanding how dust evolves in different physical environments is therefore essential for interpreting observations across the electromagnetic spectrum and for modeling the chemistry and physics of star-forming regions. However, dust properties are not universal — they change depending on the local conditions of radiation intensity and gas density.

The research question: how does dust evolve under extreme radiation?

The primary objective was to constrain the dust grain properties (size distribution, composition, structure) across multiple PDRs with different physical conditions, and then understand how dust responds to changes in UV irradiation and gas density.

This required studying not just one object, but a systematic sample of PDRs spanning a range of conditions: from the iconic Horsehead Nebula (a relatively moderate PDR) to more intensely irradiated regions like Orion and Carina. By comparing dust properties across these environments, we could disentangle intrinsic variations from environment-driven evolution.

My approach: systematic comparison across multiple environments

Multi-wavelength observational campaigns: I analyzed data from multiple space and ground-based observatories: Herschel (far-infrared), Spitzer (mid-infrared), and ground-based facilities. Each wavelength range probes different aspects of the dust population — mid-infrared emission traces warm, small grains near the illuminated surface, while far-infrared emission probes the bulk of the cold dust mass deeper in the cloud.

Spatially-resolved analysis: Rather than treating each PDR as a single point, I performed spatially-resolved analysis to track how dust properties change with depth into the cloud (i.e., with distance from the illuminating star). This required careful handling of the varying spatial resolution across different instruments and wavelengths.

Sophisticated dust modeling: I used state-of-the-art dust models (THEMIS — The Heterogeneous dust Evolution Model for Interstellar Solids, and DustEM) that treat dust as a population of grains with different sizes, compositions, and optical properties. These models can predict emission spectra for any given dust mixture, allowing forward modeling from dust properties to observables.

Radiative transfer in PDR environments: I coupled the dust models with PDR codes (Meudon PDR code, DustPDR) that self-consistently compute the UV radiation field, gas temperature, and chemistry as functions of depth into the cloud. This was essential because the local radiation field determines which grains are destroyed and which survive.

Systematic comparison across objects: By applying the same methodology to multiple PDRs, I could identify which variations in dust properties were robust across environments and which were specific to local conditions. This comparative approach is analogous to studying the same phenomenon across multiple datasets to distinguish signal from noise.

Key findings: small dust grains destroyed by UV radiation

Depletion of nano-grains in irradiated regions: A key finding was that the smallest dust grains (nano-grains, with sizes below ~10 nanometers) are systematically depleted in the UV-illuminated zones of PDRs. This depletion increases with the intensity of the radiation field — the more intense the UV, the fewer small grains survive. This is consistent with theoretical predictions that small grains are destroyed by UV photons through processes like photodissociation and sputtering.

Evolution with physical conditions: I quantified how the dust size distribution changes as a function of both UV intensity and gas density. Higher-density regions provide some shielding for small grains, while low-density, highly-irradiated zones show the most dramatic depletion. This has important implications for understanding dust evolution in galaxies with different star formation intensities.

Implications for future observations: These results were instrumental in preparing for observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). I was an extended core team member of the PDRs4All Early Release Science program, and my work helped the collaboration secure this successful program and interpret the unprecedented JWST data of the Orion Bar.

Publications: This work resulted in two first-author papers in Astronomy & Astrophysics (2020, 2022), establishing a framework for interpreting dust emission in PDRs that continues to be applied to JWST observations.

Project 3: When Dust Changes, Gas Feels It

Impact of Dust Evolution on Gas Heating in PDRsThe scientific context: linking dust and gas physics

In the previous project, I established that dust properties evolve significantly in PDRs — particularly that small grains are depleted in UV-irradiated zones. But dust and gas in the interstellar medium are not isolated systems; they are intimately coupled through multiple physical processes.

One of the most important coupling mechanisms is the photoelectric effect: when UV photons hit dust grains, they can eject electrons from the grain surface. These energetic "photoelectrons" then collide with gas atoms and molecules, transferring their kinetic energy and heating the gas. This is the dominant heating mechanism for neutral gas in many astrophysical environments.

Here's the critical link: the photoelectric heating rate depends strongly on the dust grain surface area. Small grains have much more surface area per unit mass than large grains (geometry dictates this — surface area scales as r², volume as r³). If small grains are depleted, as I found in Project 2, then the total grain surface area decreases, and so does the photoelectric heating rate. This could have profound implications for gas temperatures throughout PDRs and beyond.

The research question: how does dust evolution affect gas heating?

The goal was to quantify how the dust evolution observed in PDRs affects the thermal balance of the gas, specifically the photoelectric heating. This required propagating the dust property constraints from Project 2 through gas physics models to predict observable consequences.

A secondary objective was to test whether this could help resolve a long-standing problem: models of PDRs have historically struggled to reproduce the observed gas temperatures — they often predict temperatures that are too low, suggesting that some heating mechanism is missing or underestimated.

My approach: integrating dust properties into gas models

Coupling dust and gas models: I integrated the evolved dust properties (from Project 2) into PDR codes that compute the gas thermal balance. This required modifying how the photoelectric heating rate is calculated, using the actual constrained dust size distributions rather than standard assumptions.

Self-consistent modeling: The calculation is non-trivial because dust properties, UV field, and gas temperature are all coupled. The UV field determines which grains survive; the surviving grains determine the heating rate; the heating rate determines the gas temperature; and the gas temperature affects chemistry and dynamics. I implemented an iterative approach to achieve self-consistency.

Predictions for gas emission lines: The gas temperature directly affects the intensity of emission lines from atoms and molecules. I computed predicted line intensities for key diagnostic species (like [C II] at 158 μm) that can be compared with observations from facilities like Herschel and SOFIA.

Key findings: a puzzle that deepens, pointing to missing physics

Reduced gas heating: As expected, accounting for the depletion of small grains leads to significantly reduced photoelectric heating rates — by factors of 2-5 in the most irradiated zones. This reduction is substantial and has measurable consequences for predicted gas temperatures and emission line intensities.

A puzzle deepens: Interestingly, this result actually worsens the long-standing "heating problem" in PDRs. If anything, models already predicted too little heating; now, with evolved dust, they predict even less. This is not a failure — it's a valuable result that points toward missing physics. The finding motivates the search for additional heating mechanisms (mechanical heating from turbulence, cosmic ray heating, or others) that must be operating in these environments.

JWST preparation: This work was directly relevant for the PDRs4All collaboration. By quantifying how dust evolution affects gas observables, we could better interpret the combined dust and gas observations from JWST. The predictions I made are now being tested against actual JWST data of the Orion Bar.

Publication: Published in Astronomy & Astrophysics (2021), this paper bridges dust physics and gas physics, demonstrating the importance of treating the interstellar medium as a coupled system rather than studying dust and gas in isolation.

Project 4: Finding Hidden Patterns in the Milky Way

Detecting Kinematic Structures with Wavelet Analysis

The scientific context: hidden structures in stellar motions

The solar neighborhood — the region of the Milky Way within a few hundred parsecs of the Sun — contains thousands of stars moving in all directions. But these motions are not random. Hidden within the apparent chaos are kinematic structures: groups of stars that share similar velocities, indicating a common origin or dynamical history.

These structures are fossils of the Galaxy's past. Some are remnants of dissolved star clusters; others are caused by resonances with the rotating spiral arms or the central bar of the Milky Way. Detecting and characterizing these structures tells us about galactic dynamics, star formation history, and the gravitational potential of our galaxy.

The challenge is that these structures are subtle overdensities in velocity space, embedded in a noisy background of field stars. Detecting them requires sophisticated statistical techniques that can identify localized features at multiple scales while accounting for observational uncertainties and Poisson noise.

The research question: can we detect kinematic structures robustly?

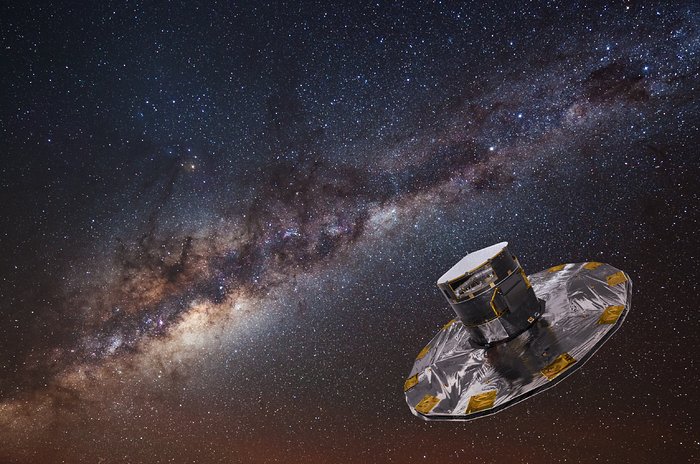

The objective was to apply wavelet analysis to the largest available stellar kinematic dataset (combining Gaia DR1/TGAS and RAVE surveys, over 55,000 stars with precise 3D velocities) to detect and validate kinematic structures in the solar neighborhood.

A key requirement was statistical rigor: any detected structure needed to be validated against the possibility of being a spurious detection due to noise. The previous studies had used smaller datasets or less robust validation methods.

My approach: wavelet analysis with Monte Carlo validation

Data preparation and quality control: I worked with a catalog of stellar positions and velocities, but not all measurements are equally reliable. I implemented quality cuts based on velocity uncertainties (keeping only stars with σ_U and σ_V < 4 km/s) and parallax quality, resulting in a clean sample of 55,831 stars with well-determined space velocities. Proper data cleaning was essential — including unreliable measurements would have introduced spurious features.

Wavelet decomposition: I applied the "à trous" (with holes) wavelet algorithm — a multi-scale analysis technique that decomposes the 2D velocity distribution into different spatial scales. Unlike simple histogram binning, wavelets can detect structures of varying sizes simultaneously and provide information about both the location and scale of features. The algorithm is implemented in the MR software developed by J.L. Starck and F. Murtagh.

Poisson noise filtering: Because we have a finite sample of stars, the velocity histogram contains Poisson noise. I used the auto-convolution histogram method to filter out noise-induced features, keeping only structures that are statistically significant at the 3σ level (99.86% confidence that the structure is not due to Poisson fluctuations).

Monte Carlo validation: This was a crucial innovation. Even after Poisson filtering, structures could be artifacts of velocity measurement uncertainties — if a star's true velocity is uncertain, it might be assigned to the wrong bin, potentially creating or destroying apparent structures. I developed a Monte Carlo approach: generate 2,000 synthetic datasets by randomly perturbing each star's velocity according to its measurement uncertainty, run the full wavelet analysis on each realization, and track which structures appear consistently. Only structures detected in >50% of realizations were considered robust.

Structure characterization: For each validated structure, I extracted parameters: position in velocity space (U, V), size, number of member stars, and statistical significance. I compared detected structures with the literature to identify known moving groups and flag potentially new discoveries.

Key findings: validating known structures and discovering a new one

Robust detection of known structures: The analysis successfully recovered all major kinematic structures previously identified in the solar neighborhood: the Pleiades, Hyades, Sirius, Coma Berenices, Hercules, and others. The positions and sizes matched literature values, validating the methodology.

Discovery of a new kinematic structure: Among the robust detections was a previously unreported overdensity at (U, V) ≈ (37, 8) km/s. This structure passed all validation tests — it appears consistently across Monte Carlo realizations and is statistically significant at >3σ. Its origin remains to be explained, possibly linked to resonances with the Galactic bar or a dissolved cluster.

Methodological contribution: The Monte Carlo validation framework I developed provides a template for future studies using improved data (Gaia DR2, DR3, and beyond). The approach of propagating measurement uncertainties through the entire analysis pipeline is now standard practice in kinematic studies.

Impact: Published in Astronomy & Astrophysics (2017), this paper has been cited 33+ times and contributed to the foundation for subsequent studies using Gaia data. The wavelet + Monte Carlo methodology has been adopted by other groups studying galactic dynamics.